Wendell Berry introduces us to a young man I understand to be a mainstay of his fiction, Nathan Coulter, with the word ‘dark’:

Dark. The light went out the door when she pulled it to. And then everything came in close around me, the way it was in the daylight, only all close. Because in the dark, I could remember and not see. The sun was first, going over the hill behind our barn. Then the river was covered with the shadows of the hills. Then the hills went behind their shadows, and just the house and the barn and the other buildings were left, standing black against the sky where it was still white in the west.

I hedge my description with the words ‘(as) I understand’, because Nathan Coulter: A Novel is my own rather carefully chosen introduction to Wendell Berry the writer, Wendell Berry the novelist, and Coulter and his kin. That first paragraph sets some of Berry’s major literary artifacts in their place, what with its mention of darkness and light, house and barn, sun, hills, river, and shadows. Always shadows.

As I’d been warned, the pace of Berry’s fiction-writing pen is a slow one, perhaps as befits the pace of the rural Kentucky life he describes. Yet slow never need mean shallow, in fact just the opposite.

As I’d been warned, the pace of Berry’s fiction-writing pen is a slow one, perhaps as befits the pace of the rural Kentucky life he describes. Yet slow never need mean shallow, in fact just the opposite.

Already, a newbie to Berry and Berrian fiction, this reader can see that things in Berry’s world—in Nathan Coulter’s world—are rarely as they appear to be, seldom as an outsider might presume them to be on first evidence. The holy are not necessarily so, the profane more insightful and even merciful than expected, the shadows sometimes full of light as well as darkness.

I can hardly wait for whatever happens next.

Elizabeth George Speare’s fine novel of a Barbados-born teenager who lands in chilly New England—a bit frosty in more ways than one—makes for fine young adult reading. It was also a treat for this comparative geezer, who will soon live near Wethersfield, Connecticut, the principal location in which this novel’s drama plays out.

Elizabeth George Speare’s fine novel of a Barbados-born teenager who lands in chilly New England—a bit frosty in more ways than one—makes for fine young adult reading. It was also a treat for this comparative geezer, who will soon live near Wethersfield, Connecticut, the principal location in which this novel’s drama plays out. work (an updated edition appeared in 2012) in the Era of Trump amid the Rise of the New Nationalisms. As a sympathizer with Zakaria’s internationalism, I acknowledge that the sureties he dispenses are now all contested. Or, perhaps, shouted down. We are the worse for it.

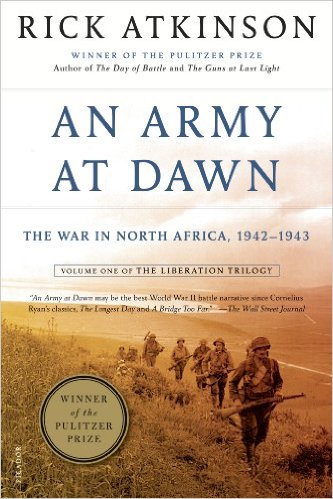

work (an updated edition appeared in 2012) in the Era of Trump amid the Rise of the New Nationalisms. As a sympathizer with Zakaria’s internationalism, I acknowledge that the sureties he dispenses are now all contested. Or, perhaps, shouted down. We are the worse for it. In The Day of Battle, as elsewhere, Atkinson’s writing is not only fueled by the very best research. It also goes down smoothly as such a tale can.

In The Day of Battle, as elsewhere, Atkinson’s writing is not only fueled by the very best research. It also goes down smoothly as such a tale can.

In his introduction to The Coldest Winter, the author alludes to the ‘colossal gaffe’ of Secretary of State Dean Acheson’s omission of South Korea when drawing America’s Asian defense perimeter. Sadly, the Korean Conflict was to offer a strong roster of competitors for ‘greatest colossal gaffe’ status. Per Halberstam’s statistics, the chaotic war without the title would claim 33,000 American lives alongside of 415,000 South Koreans and perhaps a million and a half Chinese and North Koreans.

In his introduction to The Coldest Winter, the author alludes to the ‘colossal gaffe’ of Secretary of State Dean Acheson’s omission of South Korea when drawing America’s Asian defense perimeter. Sadly, the Korean Conflict was to offer a strong roster of competitors for ‘greatest colossal gaffe’ status. Per Halberstam’s statistics, the chaotic war without the title would claim 33,000 American lives alongside of 415,000 South Koreans and perhaps a million and a half Chinese and North Koreans.

True to its subject, the book is a gentle read. It invites the reader into to increasing levels of understanding of this odd people, The Amish. Though it brings to bear upon its topic social-scientific, historical, and religious-studies rigor, it does so with a profound respect for the Old Order Amish themselves. As a result, the Amish come into clearer focus as fellow human beings who have chosen a certain lifestyle in a world that offers them alternatives. Caricatures fade amid the careful instruction of the authors.

True to its subject, the book is a gentle read. It invites the reader into to increasing levels of understanding of this odd people, The Amish. Though it brings to bear upon its topic social-scientific, historical, and religious-studies rigor, it does so with a profound respect for the Old Order Amish themselves. As a result, the Amish come into clearer focus as fellow human beings who have chosen a certain lifestyle in a world that offers them alternatives. Caricatures fade amid the careful instruction of the authors.