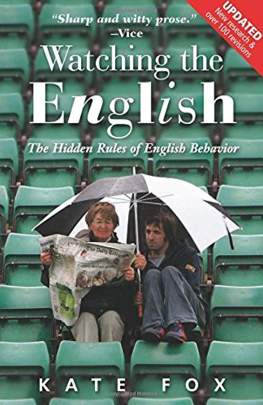

Kate Fox’s 2008 (updated and revised, 2014) exercise in English national self-flagellation  is what we used to call a ‘sprawling’ work.

is what we used to call a ‘sprawling’ work.

But that might be to suggest that a single gripping plot line traceable through the book’s 228 pages envelopes an unusually vast cast of characters or detours remarkably into literary tributaries, like one of those fat Russian novels that nonetheless retains its power to draw the reader through, page after page.

That is not the case here.

But hold on, don’t get your knickers in a twist. I mean this review to shed a positive light on a thoroughly enjoyable book of which I have already clocked two front-to-back readings.

In truth ‘sprawling’ might be a bit of (learned) English understatement of a deficiency when ‘unedited’ would express the thing with more candor.

If ever there were need for an editor with a savage glint in her eye, this book could serve as Exhibit A for the utility of that craft. Yet an editor might have spoiled half the fun, perhaps even turning Watching the English into the kind of book that Kate Fox would not be very good at writing.

As a Yank who in the 1990s spent four delightfully memorable years in England, I found myself asking at regular intervals as I read, ‘What exactly is this book?’

Is it a manual for technical consultation as occasion demands? Is it bathroom reading—I mean this in the very best sense, suspecting that the author would understand the compliment—for repeated consultation when a pinch of distracting hilarity is most to be appreciated? Is it a travel guide, to be read quickly in preparation for journeying among the English, with an eye that gleans rather than methodically harvesting of systematic truth?

I go for the bathroom reading option, though the book would easily prove its merits on any of the other counts.

But if you insist on reading the book front-to-back, here’s what you simply must do: Start at the back.

I’m not kidding.

The author’s twenty-three page conclusion, entitled ‘Defining Englishness’, succinctly—well, sort of—provides the piece that was missing for the two hundred page-turns before it. I’m convinced that it could serve as a reader’s orientation that would enhance the value of Fox’ rambling exploration of ‘the grammar of Englishness’.

For that is what this anthropological participant-observer among her own tribe—there’s an oxymoron waiting for scrutiny, which in fact the author provides along the way—has sought to place into our hands: a grammar of Englishness, a sort of root-level exploration of why the entire world of English quirks and agonies hangs together in a system that makes sense and can be described. She wants to trace the unwritten and invisible rules that stand behind the life and behavio(u)r of these very strange people of hers. In this admittedly Anglophile readers eye’s, she has done a pretty good job succeeding at a complex task. ‘Animals’, she reminds us, ‘just do these things; humans make an almighty song and dance about it. This is known as “civilisation”.’

It’s possible, even if you have no particular opinion of the English, that reading this book on a sunny day—should you step outside your bathroom to do so—could cause you to like them quite a lot. For this American reader, Fox’ rambling ethnography brought frequent smiles of appreciation and a not infrequent series of ‘Oh, so that’s what was happening that time when …’.

A few unscientifically chosen samples of Foxian paragraphs may provide a sense for where she will take you when you read Watching the English.

On ‘Emerging Talk-Rules’:

The mobile phone has, I believe, become the modern equivalent of the garden fence or village green. The space-age technology of mobile phones has allowed us to recreate the more natural and human communications patterns of pre-industrial society, when we lived in small, stable communities and enjoyed frequent ‘grooming-talk’ with a tightly integrated social network of family and friends.

On ‘The Moat-and-Drawbridge Rule’:

But an Englishman’s home is more than just his castle, the embodiment of his privacy rules, it is also his identity, his main status-indicator and his prime obsession. And the same goes for English women. This is why a house is not just something that you passively ‘have’, it is something that you ‘do’, something that you ‘work on’.

On ‘Humour Rules’:

‘If, as someone once said, ‘Comedy is tragedy plus time’, it would seem that the time required for the English to turn tragedy not humor is about a nanosecond.

On ‘Post-mortem rules’ among the horsey set:

The unwritten rules governing such conversations express the tacit understanding that a horse very rarely loses a race because it is not fast enough. If you eavesdrop on a few post-mortem conversations (a most amusing pastime, I recommend it), you will soon find that horses lose races because they get a bad draw, get upset in the stalls, miss the break, get boxed in, get bumped, can’t act on the going, fail to settle, lose their action on a sharp bend, run wide, need the race, have got jaded from too much racing, should have gone for the gap, should have taken the outside, saw daylight too soon, didn’t get a run until too late, might try him over a mile, might try him in blinkers and got bags of stamina and sure to improve next time out and ran a great race, really, considering … You may have some difficulty keeping a straight face, but what you must not do, ever, is even to hint that an owner’s horse might possibly have been beaten by twenty lengths and come fourteenth because it was up against thirteen better horses.

On ‘Ambivalence Rules’ when food is in question:

‘Loveless marriage’ is not an entirely unfair description of the English relationship with food, although marriage is perhaps to strong a word: our relationship with food and cooking is more like a sort of uneasy, uncommitted cohabitation. It is ambivalent, often discordant, and highly fickle. There are moments of affection, and even passion, but on the whole it is fair to say that we do not have the deep-seated, enduring inborn love of food that is to be found among our European neighbors, and ended in most other cultures … Among the English, such an intense interest in food is regarded by the majority as at best rather odd, and at worst somehow morally suspect—not quite proper, not quite right.

Further, English males are subject to cultural legislation entitled the ‘English males, animation and the three-emotions rule’. It allows them ‘surprise, providing it is conveyed by expletives; anger, generally communicated in the same manner; and elation/triumph, which again often involves shouting and swearing’. The supremely important ‘Grooming-Talk’ is ‘the verbal equivalent of picking fleas off each other or mutual back-scratching.’ On ‘The Embarrassment Rule’, ‘In fact, the only rule one can identify with any certainty in all this confusion over introductions and greetings s that, to be impeccably English, one must perform these rituals badly. One must appear self-conscious, ill-at-ease, stiff, awkward and, above all, embarrassed. Smoothness, glibness and confidence are inappropriate and un-English … If you are socially skilled, or come from a country where these matters are handled in a more reasonable, straightforward manner (such as anywhere else on the planet), you may need a bit of practice to achieve the required degree of embarrassed, stilted, in competence.’

Although Fox claims she is writing for the ‘intelligent layman’ and not for fellow academics—she is an anthropologist, in case that previously mentioned detail has escaped us along the way—she labors ‘manfully’ in her introduction to show that she has thought through the ethical and methodological quandaries of pulling off just this kind of participant observation among her very own people.

Words like ‘long’ and ‘tedious’ recur in reviews of Watching the English, never a promising advertisement of a popular work. I suspect these result from a mistaken judgment about the book’s genre. Fox has given us toilet reading of a brilliant and insightful kind. Depending on your constitution, it may take you years to get through it, but it’ll prove faithful in some very tender moments.

Start at the back.

Leave a comment